Here is a weird question that I have often asked: Is Methodological Naturalism a valid method of inquiry for Christians?

I know . . . cardinal sin. I have started with a hard word. Just hang with me. I promise this goes somewhere special.

Methodological Naturalism Defined

First, let me define exactly what I mean. Methodological naturalism, for those of you who don’t know, is an approach to scientific inquiry that seeks to understand the natural world through natural causes and explanations, without invoking supernatural or divine causes. Please understand, this is distinct from Philosophical Naturalism which assumes that God does not exist and this reality provides a basis for Methodological Naturalism. Methodological Naturalism has no opinion about God at all. In other words, it assumes that natural causes can explain all natural phenomena. For example, a person whose car won’t start would look for natural explanations such as gas, battery, starter, spark plugs, and the like rather than supernatural causes such as demonic intervention. Similarly, a physician treating a patient would rely on medical science and natural remedies to diagnose and treat the illness, rather than prayer or spiritual healing. Methodological naturalism has been widely accepted in modern science as it has been highly effective in understanding and explaining natural phenomena. With it, for better or worse, humanity has excelled in areas such as mechanics, electronics, space exploration, and medical advancements.

Now, back to my original question (changed just a bit): Isn’t methodological naturalism the responsible way for Christians to approach inquiry into all our understandings and experiences? Shouldn’t we assume no outside (miraculous, paranormal, divine) direct influence in situations we observe and investigate?

For example, if we hear a banging in our house in the middle of the night, we assume that there is a natural explanation for this banging. Maybe it is another family member, a pet, the wind, gravity, or even a burglar? It is only if and when all naturalistic phenomena have been exhausted that we resort to a less likely unnatural spiritual or supernatural explanation.

Of course, I have a graphic for this (you know how married my mind is to graphics!):

Methodological Naturalism Applied

Your car won’t start:

What did it mean: No gas

How does it apply to you: You have to find a way to get gas, walk, or not go anywhere.

It’s pretty simple. Isn’t this the way we all engage the world? Is it wrong for Christians?

I read this about Methodological Naturalism recently:

“Methodological naturalism is not inherently Christian or non-Christian. It is a philosophical approach to scientific investigation that focuses on natural causes and explanations for phenomena, and it does not necessarily conflict with Christian beliefs. Many Christians accept methodological naturalism as a useful tool for scientific inquiry and discovery, while also recognizing that it has limitations and does not provide a complete picture of the world.”

Sounds good, right?

Problems with Methodological Naturalism

Not so fast. I used to believe this, but I have been rethinking this. Methodological Naturalism can be problematic if it is applied as a strict philosophical dogma in inquiry. As a system, it excludes any consideration of supernatural or divine not just in intervention, but in providential involvement as well. As Christians, we believe that God is the creator of the natural world and through his creative process, he has created it in such a way that it follows natural processes. But we also believe that He is actively involved in it. Limiting understanding and investigation to naturalistic explanations misses important aspects of the world that God has created and your life he is always involved in.

The Homiletical Process

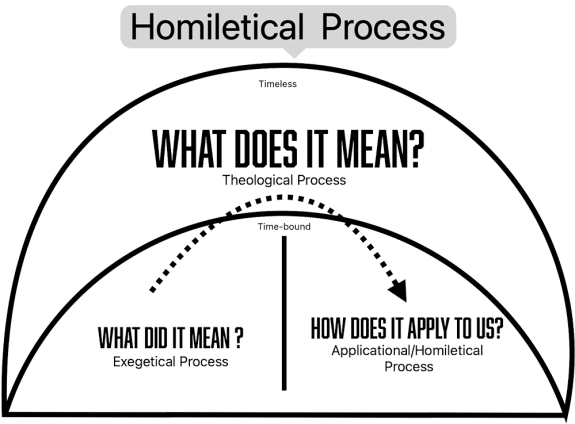

Let’s look at this issue from the perspective of biblical interpretation:

As you can see, our process of interpreting the Bible has many similarities to Methodological Naturalism. We call our method “Authorial Intent Hermeneutics” (hermeneutics is simply a fancy word for “method of interpretation”) or the “Homiletical Process” (homiletical, as well, is a fancy word for “sermon or message delivery”). We believe the first step in this process is to understand what the author meant to his original audience in the original situation.

My point is that when studying the Scriptures, we always start the same way someone who follows Methodological Naturalism would start. We do diligence to understand the Bible in its original context. However, before we move to the question “how does it apply to us?” we take a trip into the eternal and providential. We ask “what does it mean?” not simply because we believe God is the ultimate author of Scripture, but because we believe God is an active God, involved in all things. We believe that the Scriptures can apply to us because we believe in eternal principles. The Scriptures have a special place only in that they are part of a special message that God gave through his intercession. Therefore, we ask What does this mean for all people, of all times, everywhere? Sometimes the eternal principle is evident, obvious, and specific, but many times it is general and relative to the broader contexts. Sometimes the Scripture will prescribe something that man should do, and sometimes it just describes what some individual did. In both, we see God’s providence. For example, when we are told by the book of John that “the one who Jesus loved” outran Peter to the tomb, we may not have an eternal principle saying that we should learn how to run faster for God, but we do know that God, in his providence, wanted us to know this part of the story. It’s incidental, yet providential at the same time.

Providential Naturalism Defined

Let me try to define providence since it is a central idea for which I am trying to make an argument. Providence refers to the idea that God is actively involved in the world, directing all events, big and small, and working out His plan. It is the belief that God is not distant or detached from the affairs of the world but is rather intimately involved in every aspect of life, guiding and sustaining all things according to His will. Providence can be seen as the way in which God exercises His sovereignty over creation, bringing about His purposes and fulfilling His promises. It encompasses the idea that God is always working for the good of those who love Him, in the midst of circumstances that bring us great pain and pleasure, and when one’s car breaks down. Ultimately, the concept of providence affirms God’s love, wisdom, power, and goodness, and gives believers confidence that we can trust in Him to guide and care for them in all aspects of life. So far so good?

Now, Christians who believe and follow the Methodological Naturalistic process argue that we should only turn to supernatural options of direct intervention when we have exhausted the natural options and found them wanting. Of course, we can and should always see God’s providential movements as the ultimate cause or beginning as we reflect on the moral reasoning behind all events, but Methodological Naturalism is their umbrella philosophy that dictates their first steps in everything. For the Methodological Natralist Christian, most of the events that happen to us on a daily basis are mundane and meaningless. We do not need to think of any transcendent reason for these events.

While I appreciate and sympathize with this method as it does not leave God completely out, I don’t believe that this is the best process for Christians. Now, maybe it is my Calvinism or maybe it is just my strong view of God’s immanence (i.e. God is present in all the happenings of our life), but I believe that we should actively see God in everything, even the mundane. Why? Because he is there. The hermeneutical process that we use to interpret the Bible should be the process that we use to interpret all things. I think we can call our method of inquiry Providential Naturalism, thereby recognizing God’s presence even in the natural and most mundane things in our life.

Providential Naturalism Applied

For example, if we hear a banging in our house in the middle of the night, we assume that there is a natural explanation for this banging. Maybe it is another family member, a pet, the wind, gravity, or even a burglar? It is only if and when all naturalistic phenomena have been exhausted that we resort to a less likely spiritual or supernatural explanation for the noise. So far, this looks just the same as Methodological Naturalism. But what I am proposing is that we start with the assumption “God done it,” but that we see God’s will unfolding even when we find out that the noise was a cat.

So we take it through this process just the same:

I believe it is important that we see God In everything, for better or worse, knowing that he is not a distant God who cheerleads as we function in the world he has created, but one who is intimately involved in everything. He is a Psalm 119 God.

Just read this:

Psalm 119

1 You have searched me, Lord,

and you know me.

2 You know when I sit and when I rise;

you perceive my thoughts from afar.

3 You discern my going out and my lying down;

you are familiar with all my ways.

4 Before a word is on my tongue

you, Lord, know it completely.

5 You hem me in behind and before,

and you lay your hand upon me.

6 Such knowledge is too wonderful for me,

too lofty for me to attain.

7 Where can I go from your Spirit?

Where can I flee from your presence?

8 If I go up to the heavens, you are there;

if I make my bed in the depths, you are there.

9 If I rise on the wings of the dawn,

if I settle on the far side of the sea,

10 even there your hand will guide me,

your right hand will hold me fast.

11 If I say, “Surely the darkness will hide me

and the light become night around me,”

12 even the darkness will not be dark to you;

the night will shine like the day,

for darkness is as light to you.

13 For you created my inmost being;

you knit me together in my mother’s womb.

14 I praise you because I am fearfully and wonderfully made;

your works are wonderful,

I know that full well.

15 My frame was not hidden from you

when I was made in the secret place,

when I was woven together in the depths of the earth.

16 Your eyes saw my unformed body;

all the days ordained for me were written in your book

before one of them came to be.

17 How precious to me are your thoughts,[a] God!

How vast is the sum of them!

18 Were I to count them,

they would outnumber the grains of sand—

when I awake, I am still with you.

Does that sound like God is on the outside looking in or on the inside carrying us? I think the second.

20 replies to "This Calvinist’s View of Methodological Naturalism"

Hello, Michael!

In what way does this version of providential naturalism overcome the challenge of relegating God to superfluity? If there is a “natural” explanation available for something (your cat thumping around, for example), there doesn’t appear to be any necessity of appealing to an order of causation beyond natural causes – Occam’s Razor, etc. One may legitimately conclude on this model of providential naturalism that God is a hypothesis of which we have no need.

I’m not sure I understand. I suppose my view would attempt to avoid the deistic type philosophy where the Lord is on the outside of our circumstances and it is his will just to let them go. I’m am saying not only are his thoughts of us continual, but his activity with us is as well. Therefore, his ultimate causation brings me comfort, not just in the creation of a paradigm of function, but an intricate detailing of everything, while using secondary causes.

Okay. For the sake of understanding, let’s unpack this differently.

There is a common narrative which tried to establish the roots of naturalism in ancient Greece, when philosophers began to explain reality in terms of elements rather than myths. On this version of events, it is supposed, the history of science shows us that progress can only be made when science is unencumbered by religious dogma and brackets supernatural causes from consideration.

The problem is that many of the naturalist philosophers to whom this narrative will appeal for support – people like Aristotle and Galen, for example – have no problem with the supernatural, they do not oppose ‘natural’ and ‘supernatural’, but instead contrast the natural with the artificial. This was developed in the Middle Ages when philosophers like Aquinas articulated a distinction between substance and artefact. So, what we do in fact find going all the way back in the history of naturalism, is that for the most part people thought “the world is full of gods”. Natural and supernatural were not conceived of as a dichotomy of opposing forces.

But when this dichotomy was uncritically assumed by rationalists of the Enlightenment period, together with a mechanical conception of causality, theologians struggled to find a way to bring God back down to earth – when he should never have been evicted in the first place!

So, my issue here is that your version of naturalism – providential naturalism – assumes this false dichotomy between natural and supernatural, and as such it is open to “God of the gaps criticism”, which leads people like Pasteur (I think it was he), who said of God “I have no need of that hypothesis”. Better to correct the mistake right at the beginning, rather than accommodate yourself to it by assuming the false dichotomy (which you clearly do, since from what you have written above, you accept methodological naturalism on those very terms)

No. It’s the exact opposite. God is in and with the natural. That is why the best term I could come up with is providential naturalism. It is the synthesis between the two opposing positions.

I would also take issue with what your wrote here: “The hermeneutical process that we use to interpret the Bible should be the process that we use to interpret all things.”

Presumably, by hermeneutical process, here you mean the historical-critical method. But this is not the only hermeneutic available: so why should we prefer this framework over, say, the cultural-linguistic model of George Linbeck? I would also point out the irony here, because the historical-critical framework can and has been deployed to facilitate liberal projects like that of Harnack, much to the chagrin of more conservative Evangelicals. In fact, the same historical-critical method was used by Catholic scholars in the 19th century to counter liberalism and very competently demonstrate the truths of Catholicism, much to the chagrin of general Protestantism. So it is overstating the case to insist that this is a reliable method to interpret all reality, as if all reality is accessible to this very restrictive and constrained mode of inquiry

“God is in and with the natural. That is why the best term I could come up with is providential naturalism. It is the synthesis between the two opposing positions.”

Yes, you are making my point: any attempt at synthesis here implies that you are imposing strict separation between the two orders – hence your model of providentialism to try and reconcile natural and supernatural. So, unless your approach to reality is dualistic – which it clearly is – then synthesis makes no sense

Not at all. Think of it as you would traducianism with the spirit and the body. The spirit is in and with the physical. This is the way it is in all things you only separate them because what you’re arguing against separates them. You try to get them back together.

Or, conditional unity. That is a good word, because it show the unnatural, but necessary, breach between the body and the soul. Necessary only because of sin. The parallels are striking. Yet, I have the feeling we are close, but passing each other in the night.

I think we agree, in so far as we both recognise the problem of a dualistic approach to reality. But I think we disagree, in so far as I think your synthesis, though well intentioned, involves the very dualistic presumptions which are at the root of the problem in the first place (why you think there is a “necessary breach” between soul and body, for instance).

Well, only a necessary unnatural breach at death. There could be some parallels in the current issue (ie what sin did to creation, the mind, and the like), but I was not meaning to say there was a breach in our current issue we are discussing. So, I am not starting with an assumption of dualism, then bringing them together, I a just recognizing that most people are dualists and need to correct this by methodology or just the practicality of seeing it as a synthesis. That make sense?

(Perhaps that same presumption of a necessary breach also explains your Calvinist position, with the whole total depravity thing?)

Sure. It is compatibalism basically (with an edit here and there). It may sound Hegelian, and it is to some degree. Think of him living the Lord and believing the Bible and you may have it.

Hello again, Michael.

Here’s a different angle. As a Catholic, I can accept the doctrine of the real presence in the Eucharist, because of what the Church teaches about the Incarntion – namely, that in Christ human and divine natures are united, and that consequently all creation participates in the life of the Trinity. It thereby follows, that the Eucharistic elements of bread and wine are substantially changed into the body and blood, soul and divinity of Jesus Christ, despite retaining the appearance of bread and wine (substance vs accidents). If this doctrine of the real presence is rejected, then, to be consistent, one must also deny that the infant Jesus is truly divine, since a baby “doesn’t look like God”. In short, in Jesus Christ, apart from other things, a very ancient philosophical problem has been resolved: namely, how to reconcile appearance and reality.

This philosophical problem has taken many forms: the One and the many; unity and multiplicity; being and non-being; change and permanence; good and evil; spirit and matter, etc. In the Incarntion, the tendency to a dualistic ” either/or” worldview that places emphasis on one or other aspect of reality is rectified, allowing for a framework of interpretation that unites, rather than separates, the two realities of spirit and matter: Christianity presents a worldview of non-dualism that resists a binary division of reality into “either/or” categories, which makes any consistent, coherent and comprehensive system of philosophy impossible.

And when one studies the history of the Church and early Christianity, especially the first 500 or so years, when Christian theologians began to interact with Greek modes of thought, one observes that most unorthodox and heretical teachings have tended to fall on either side of this spirit/matter division: hence, Traducianism – which you mentioned above – has been condemned by the Church as a materialistic doctrine of the generation of the soul, opposed to creationism, which holds that the soul – the substantial form of the body, to borrow from Aquinas – is created directly by God.

Now consider all of the above when answering objections to Catholic doctrine. Most non-Catholic Christians, because they assume a dualistic worldview, find it difficult to comprehend how, for instance, Mary can be the “Mother of God”, if Mary is a mere mortal. They struggle to understand Papal authority, on account of the Pope is “just a fallible human being”. “How can the Church be Holy”, they insist, ” when it is full of sinners?”. On and on. But I’m sure you get the point, and can see that it is the division of reality into binary “either/or” categories which makes Catholicism difficult for many to understand and accept. When the Bible is interpreted from within the framework of a dualistic worldview (such as rationalism), you end up with a lot of internal conflict, with some groups emphasizing matter above spirit, and vice versa.

So, in my opinion, it is useless for Christians to argue amongst themselves over questions of interpretation of Scripture, without first of all addressing this more fundamental question of worldview. It’s even worse for them to then go ahead and try to develop any religious philosophy without first questioning basic dualistic assumptions on which such philosophies are based.

Concerning your longer comments about Catholicism and dualism, it’s a bit difficult for me to understand. I’m not sure if you realize how against dualism I am. As a matter of fact, I just got James Sawyer a small book on dualism and was going to do a podcast on it.

I do not reject Catholicism in any sense because of dualism. I do not reject Catholicism because I can’t reconcile the dualism and the nature of Christ. I just do not think that Christ divinity communicates to his humanity. The reason for this is not philosophical, but Soteriological. I reject it, for the same reason that Christ could not turn the stone in the bread, and therefore, forfeit the bounds of his mission, I think he still has a mission to represent humanity, and therefore is forever, in his human nature, without any communication of the divine. The communication of the divine and human nature only come in the person of Christ, not in the natures themselves. If Christ communicated his divine nature to his human nature, he could not serve as the high priest forever.

(So, if you follow my rationale here, Calvinism is a dualistic philosophy, in so far as it denigrates human nature to total depravity, showing a preference for the spiritual above the physical and material. All problems with Calvinism follow from that point; and the same basic trend or pattern can be discerened in almost objections to Catholicism)

P.S. I’m not doing Catholic apologetics here; just articulating the problem, as I see it, from what I take to be the Catholic POV

Quickly, I think we are misunderstanding each other. I have no conception of Calvinism (specifically, compatabalistic Calvinism) as being dualist. Quite the opposite. I just did not want to imply as I may have any concession of Calvinism being necessarily dualistic. Total depravity is a breach in relationship, not constitution.

Wouldn’t you say it seems odd to object to Catholic faith on the basis of a reference to Scripture which traditionally has been used in the Liturgical cycle to support the “Three Lenten Pillars” of prayer, fasting and almsgiving? And in the context, Jesus responds by saying that “Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word of God” – implying that true life is not merely human, but divine – the satisfaction of not merely physical, but spiritual hunger. Even non-Catholic Christians have generally understood Jesus’ refusal to submit to the will of Satan as a teaching about detachment from selfish desires, encouraging us to trust in the will of God. So, how you got from there to the opinion that Christ cannot continue to represent humanity if he communicates the divine nature, is not at all clear, and certainly isn’t consistent with the context, neither is it in line with the way this Scripture has been understood by Christians in the Liturgical cycle.

And in any case, even if we grant your interpretation of Jesus’ temptation, and use it as a proof text that, somehow, is supposed to show that Jesus serves as High Priest “without any communication of the divine” – even then, why think that allowing the Church a share in the divine nature would in any way abrogate the mission of Jesus? In the movie Shazam, a newly fostered young boy in search of his mother instead gains superpowers and a diabolical enemy. The hero is able to finally defeat his foe, when he enlists the help of his friends: “What good is power if it cannot be shared?”

The point is, in the same way that the hero was able to save the day by sharing his power with friends, it is not inconceivable that Jesus could communicate the divine nature and still carry out his mission as representative of humanity. So there is no contradiction involved in saying that Jesus allows us a share in his divinity while remaining our High Priest forever.

Sure it is. There are great arguments for this. But set that aside since it is only illustrative of what I said in response to you and we would have to open up not only Chalcedon theology, but the progressive development of Christology since Chalcedon’s monumental development of Christologic DNA.

Either way, on our present point we agree, even tho we get there my different directions on the same map. No reason to do anything other than appreciate our combined evidential following of the same savior, my friend.

About a century or so before the council of Chalcedon was convened, St. Athanasius the Great, Bishop Confessor, Father and Doctor of the Church, would say in his work On the Incarntion, that “God became man, so that man would become God.” I think St. Athanasius agrees with the theology of Shazam!, the film I talked about earlier, in which the hero saves humanity by sharing his powers with friends to defeat his evil enemy.

And since the theological contributions of St. Athanasius constitutes a crucial portion of that Christological DNA to which you refer – I think you will be very hard pressed to find any good arguments that show how St. Athanasius’ view of Christ’s divinity is logically inconsistent, or that it somehow contradicts the Scripture.

As for our common evidential map: perhaps we should agree that all the roads marked thereon do, eventually, lead to Rome, yeah? Haha 😉